Smithsonian conspiracy to deny Whitehead flew first

A Smithsonian conspiracy to deny Whitehead flew first – ahead of the Wrights – is now provable. A never-before-known, direct connection between denying Whitehead flew first and the designing of the “Contract” (1) (2) with Smithsonian, including the label on the Wright Flyer has been “unearthed”. This is a game-changer that establishes exactly how Whitehead’s claim was deliberately, secretly, and effectively denied, all these years. It involves plotting behind the scenes, by Smithsonian curators and influential friends of Orville Wright, to provide Orville permanent credit that he did not deserve, without regard for historical facts. It worked for 70 years.

From 1935 through 1937, Stella Randolph, Whitehead’s first researcher and original biographer, wrote a series of articles and a book about Gustave Whitehead’s flights, which predated those of the Wright brothers. Her writings received national attention, to the dismay of Orville Wright and his supporters.

Following the death of Wilbur Wright in 1912, Orville, previously considered “the lesser brother”, worked unceasingly to establish his role in first flight. Until the date of Wilbur’s death, it was Wilbur who’d been credited with being first, established in the publication of the World Almanac of 1911. Orville’s flights of December 17, 1903 had been openly admitted as failures, by both brothers. Whitehead had been ignored, as the data and article had been put together by a secret, subrosa employee of the Wrights, Thomas Edison’s former right-hand engineer, William J. Hammer. Hammer was hired by Wilbur Wright to promote the brothers as first in flight, amongst other duties. Hammer would go on to perjure himself as an independent expert during the Wright patent trials, where the World Almanac article was entered as evidence that the Wright brothers deserved “pioneer inventors” status. In the popular mind and the media, following Hammer’s PR campaigns that began in 1906, and with the support of the New York aero clubs, the Wrights were seen as “first in flight”.

Once Randolph began to publicize the earlier flights of Whitehead, friends of the Wrights organized to stamp out the claims wherever they appeared. They began to use their considerable influence to attempt to stop the Whitehead information from getting out the public, as if it was heresy. News of Whitehead’s credit was spreading like wildfire in Hollywood, in syndicated magazine articles nationwide, on a very popular coast-to-coast radio show, in ads on NYC subway cars, an article in the Reader’s Digest, and with a Harvard professor of transportation who called for a Congressional hearing on the topic. Friends of Orville felt these had to be controlled.

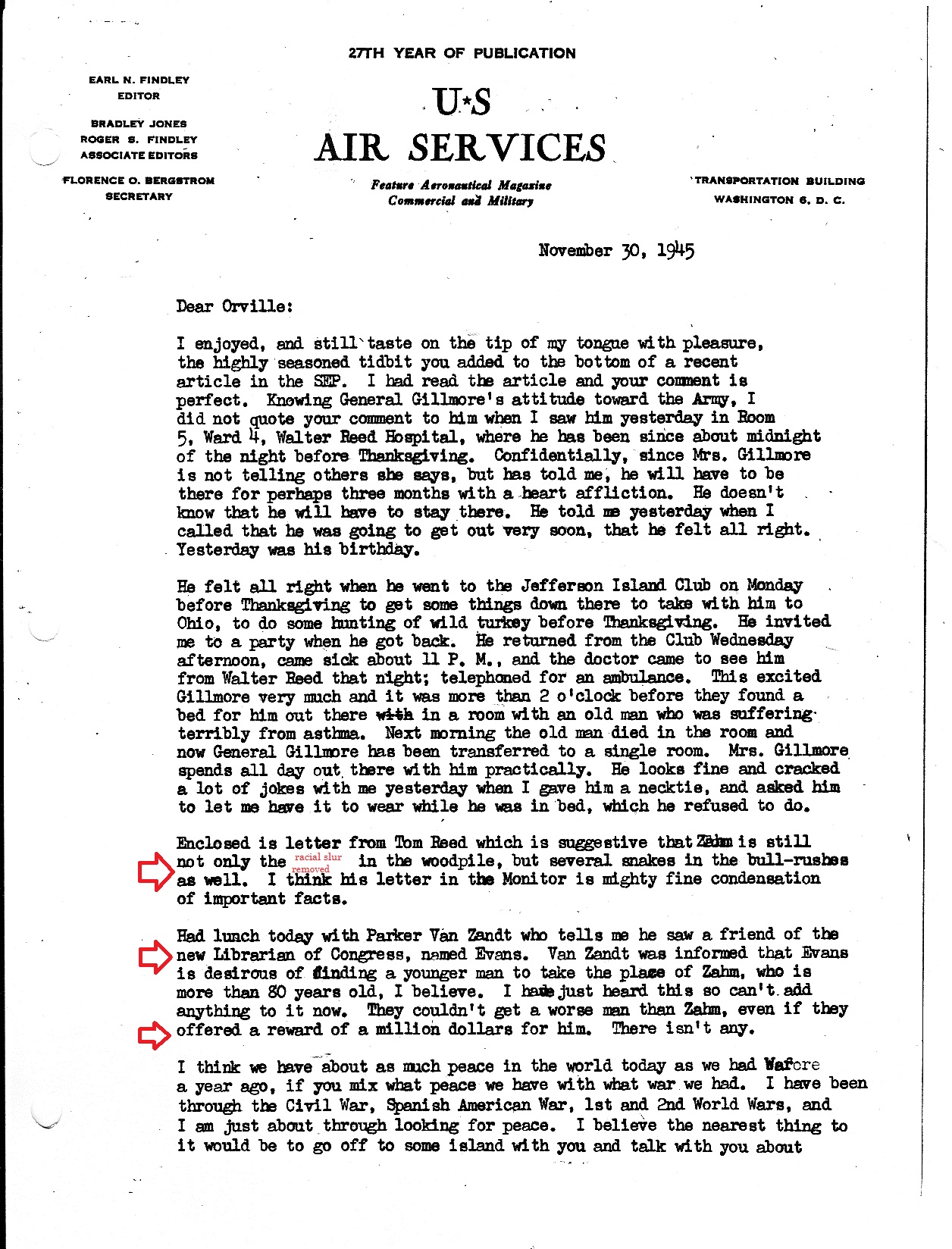

Major Lester D. Gardner and Earl Nelson Findley, two of the most influential Wright supporters, openly discussed their mutual campaign to credit Orville and wipe out Whitehead’s claim in letters that they wrote, back and forth, from 1939-1946. Both Gardner and Findley were widely recognized in aeronautical circles of the era, particularly for their close relationships with Orville Wright. Major Lester D. Gardner was the former publisher of the journal Aviation and Aeronautical Engineering in 1916, and founder of the Institute of the Aeronautical Sciences (IAS), located in New York City, in 1932. Its first honorary fellow was Orville Wright. Earl Findley was the first editor of US Air Services magazine. Findley formerly was a reporter and editor for the New York Times who became very close to the Wright brothers and the Wright family, for the rest of his life.

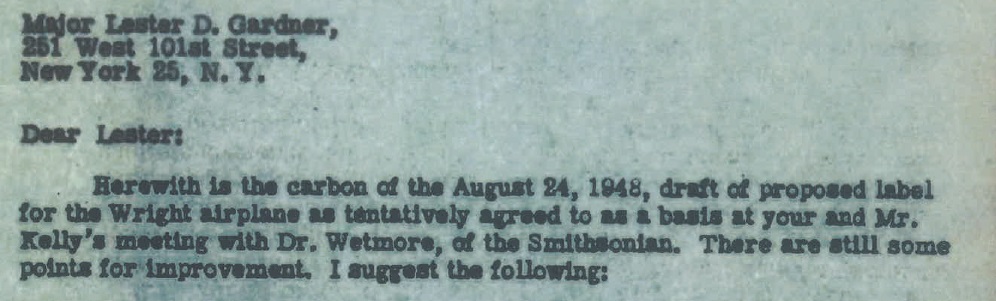

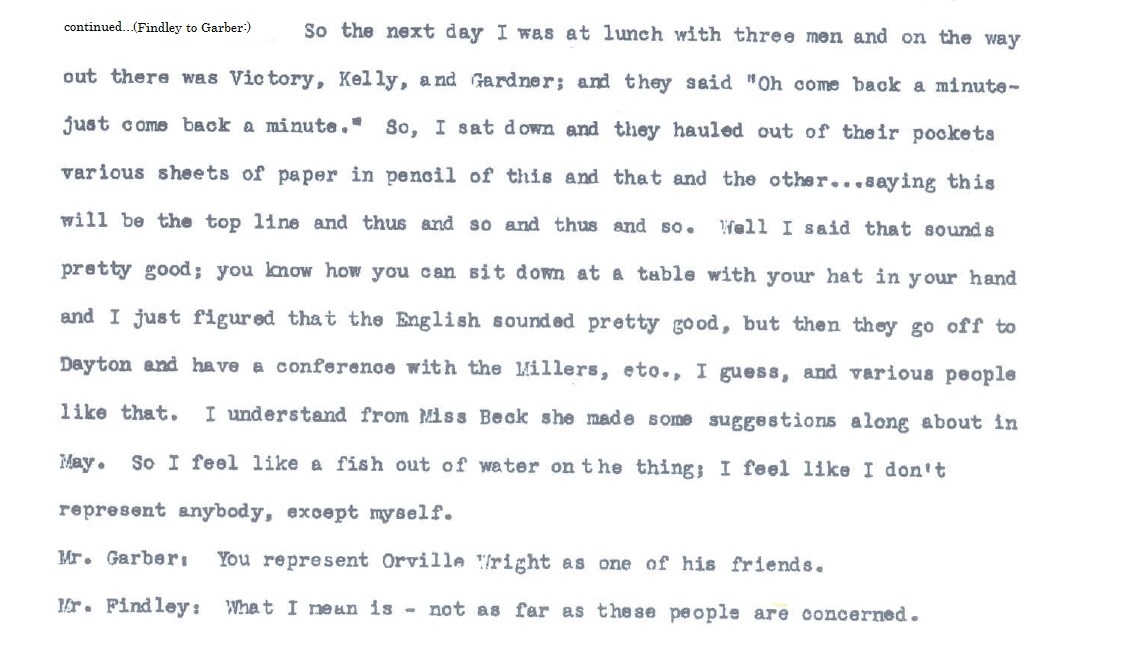

In 1939, Major Lester D. Gardner and Earl Findley orchestrated and co-produced the so-called “Stanley Yale Beach Whitehead Statement“, which denounced Whitehead could ever have flown (mentioned in the book “History by Contract” by O’Dwyer and Randolph).

Stanley Yale Beach, former Aviation Editor and supporter of Whitehead flights through 1908, is influenced to write a negative statement on GW in 1939, and he writes Major Lester Gardner to ask him to “cut out anything he doesn’t like” in the Beach statement that Gardner and Findley solicited. The draft is heavily edited by three individuals, one is Gardner, the other, Findley. Letters back and forth clearly show this.

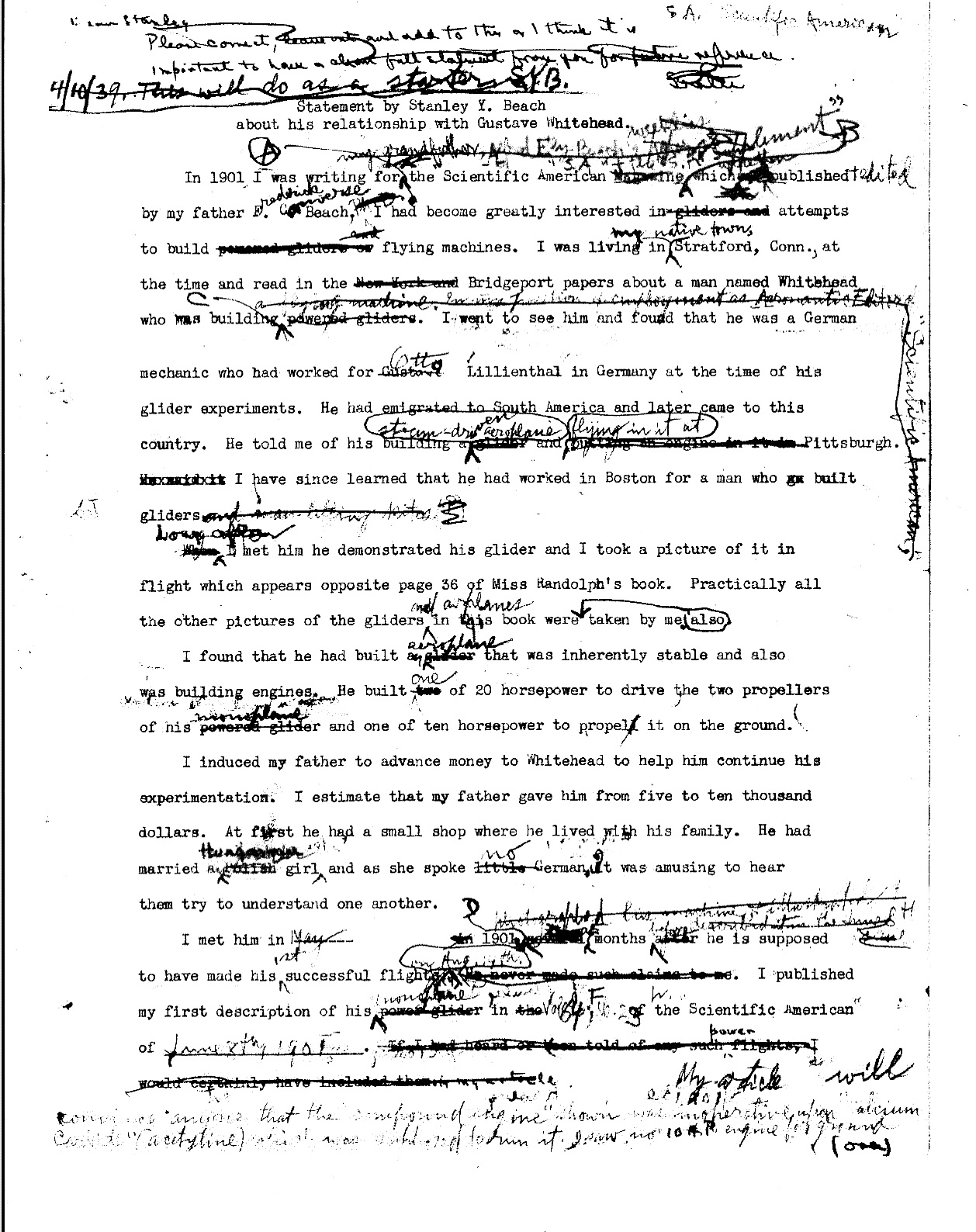

The heavily edited Beach statement drafts looked like this (pages 1 & 2 of 6):

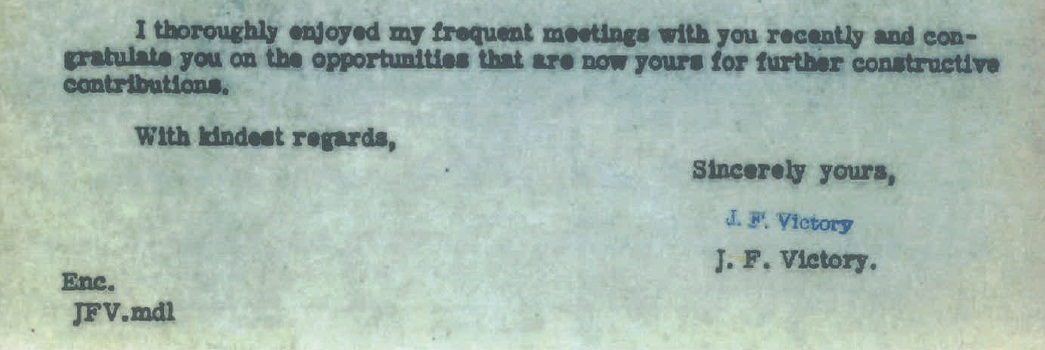

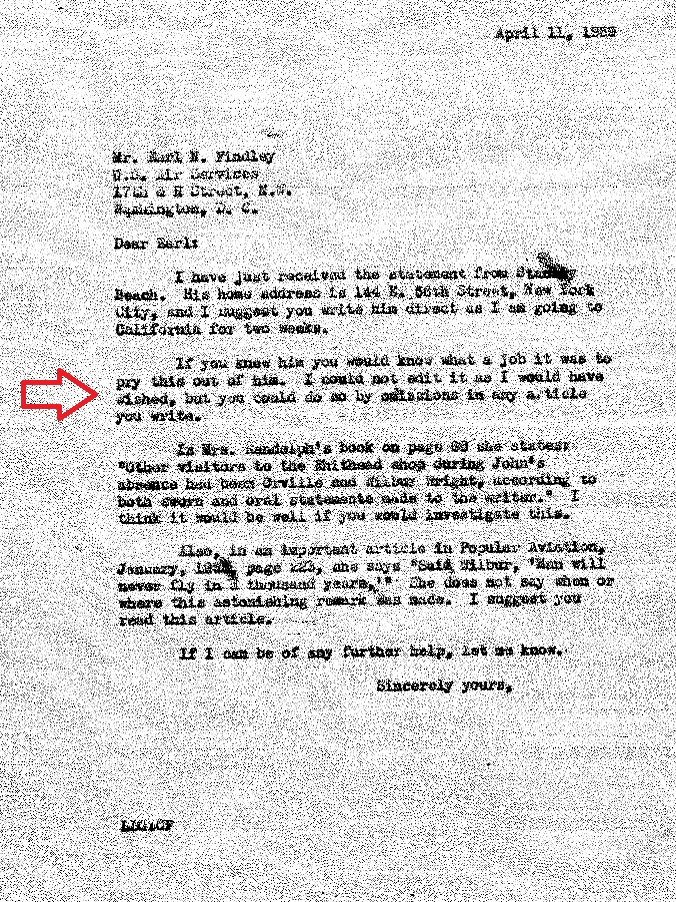

Major Lester Gardner (LDF) wrote Earl Findley on April 11, 1939, after he’d received the final draft. He said, “I have just received the statement from Stanley Beach…If you knew him you would know what a job it was to pry this out of him. I could not edit it as I would have wished, but you could do so by omissions in any article you write.” Then Gardner proceeds to express concern that Stella Randolph, in her book “Lost Flights of Gustave Whitehead” (1937) talked about an early visit to Whitehead’s shop from the Wright brothers. He wants Findley to look into it. Also, Gardner mentions Randolph used a Wright quote in her 1935 Popular Aviation article, without a citation, “Man will never fly in a thousand years” and asks Findley to read it. Gardner and Findley have become a “tag-team” to defend Orville’s desired position as first in flight and attack Whitehead researcher Randolph and supporters. They will continue this through 1948 culminating in the legal contract requiring Orville to receive that credit, to the exclusion of Whitehead, their nemesis, and all others.

Gardner writes Findley about the final Beach statement, revealing how to best use it and that he couldn’t edit it fully as he wished, but Findley can.

Both Gardner and Findley became recipients of a piece of cloth from the Wright Flyer as a token of esteem afterward(perhaps, thanks for their dogged support) from Orville.

The unpublished and unsigned Beach statement was then deliberately provided to Orville Wright, influencing him to use it as the basis for his “The Mythical Whitehead Flight” article of 1945 (below), published in Findley’s US Air Services magazine. Orville’s negative Whitehead article, denying Whitehead or his plane could ever have flown is still the “playbook” for denying Whitehead, used by Smithsonian curators through the present date.

Just a few years later, Gardner and Findley, who vowed to salvage Orville’s title and to destroy Whitehead’s claims, have now been revealed as key consultants, invited by the Smithsonian curator, Paul Garber (3), to design the final details of the “Smithsonian-Wright Agreement of 1948″ (aka “the Contract”), following Orville’s death in January, 1948. This direct connection to the creators of the denouncement of Whitehead and their subsequent influence on “the Contract” was never before known, outside of the inner circles in Smithsonian, where the documents are kept. Others who worked on the label included Wright family members; Orville’s longtime secretary, Mabel Beck (with whom he is said to have had a longterm affair); Fred C. Kelly – the Wrights first biographer and trusted, old friend; and the Smithsonian curator, Paul Garber, described as “very loyal to Orville”. The Wright Flyer label was designed by highly biased individuals based on what they felt Orville would have wanted, and what would secure credit for the first flight. No historical investigation was conducted to make the label accurate. This is clear from the correspondence and transcripts included in the Smithsonian archives concerning the planning of the Contract.

This is the required wording for the Wright Flyer* exhibit that resulted from the biased group’s efforts, which attempts to “cement” the credit for first flight for Orville, who had just died earlier that year.

“The Original Wright Brothers’ Aeroplane

The World’s First Power-Driven Heavier-than-Air Machine

In Which Man Made Free, Controlled, and

Sustained Flight

Invented and Built by Wilbur and Orville Wright

Flown by Them at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina

December 17, 1903

By Original Scientific Research the Wright Brothers Discovered The Principles of Human Flight”

[and]

“The first flight lasted only twelve seconds, a flight very modest compared with that of birds, but it was nevertheless the first in the history of the world in which a machine carrying a man had raised itself by its own power into the air in free flight, had sailed forward on a level course without reduction of speed, and had finally landed without being wrecked. The second and third flights were a little longer, and the fourth lasted 59 seconds covering a distance of 852 feet over the ground against a 20 mile wind.

Wilbur and Orville Wright(From Century Magazine**, Vol. 76 September 1908, p. 649)”

The Smithsonian-Wright Agreement of 1948, allowed Smithsonian to obtain the Wright Flyer for $1 from the Orville Wright estate. It also allowed Orville Wright heirs significant estate tax benefits. The agreement, often referred to as “the Contract”, essentially requires Smithsonian and all its affiliates, to recognize the Wright Flyer as the first airplane that flew with power, and Orville Wright as the first successful aviator. Required labels on the exhibit and required placement in the Smithsonian are included. If the Contract is broken, the Wright Flyer, the most popular exhibit at the Smithsonian, returns to the heirs. The Contract, originally kept secret from the public, was learned of and obtained by Major William J. O’Dwyer (USAF, ret.), with the help of then-Senator Lowell Weicker, Jr., in 1976. More on the “Smithsonian-Wright Agreement of 1948″ on Fox News’ site (Fox News, Apr.1, 2013)] and here (HistorybyContract.org on Wayback Machine) https://web.archive.org/web/20211206074739/http://historybycontract.org/.

The communications between Gardner and Findley concerning Whitehead’s claim as first in flight were very clear – they wanted to stamp out that claim and worked on this for 11 years following the publication of Stella Randolph’s book. They were in a position to do so, behind the scenes. Letters received and sent between Gardner, Findley, Beach, and Orville Wright, amongst others, are located at the Library of Congress, in their Gustave Whitehead collection, and the Earl Findley and Lester Gardner sections of the Papers of Wilbur and Orville Wright archives. Interestingly, and obviously by design, none of these appear on the public listing online, but they are there. Who at the LOC decided that these should be hidden from the public?

Their efforts worked, too, quite effectively, for the past (nearly) seven decades. Exposing the Gardner – Findley involvement in the development of Smithsonian-Wright Agreement of 1948 “the Contract” exposes “the agreement” with Smithsonian for what it was – a means to deny Whitehead a claim on first flight. Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum (NASM) curators and Wright supporters cannot continue to maintain that it was developed solely to fend off old Smithsonian claims that its former Secretary, Samuel P. Langley, built “the first plane capable of flight”, which had so angered Orville in 1928.

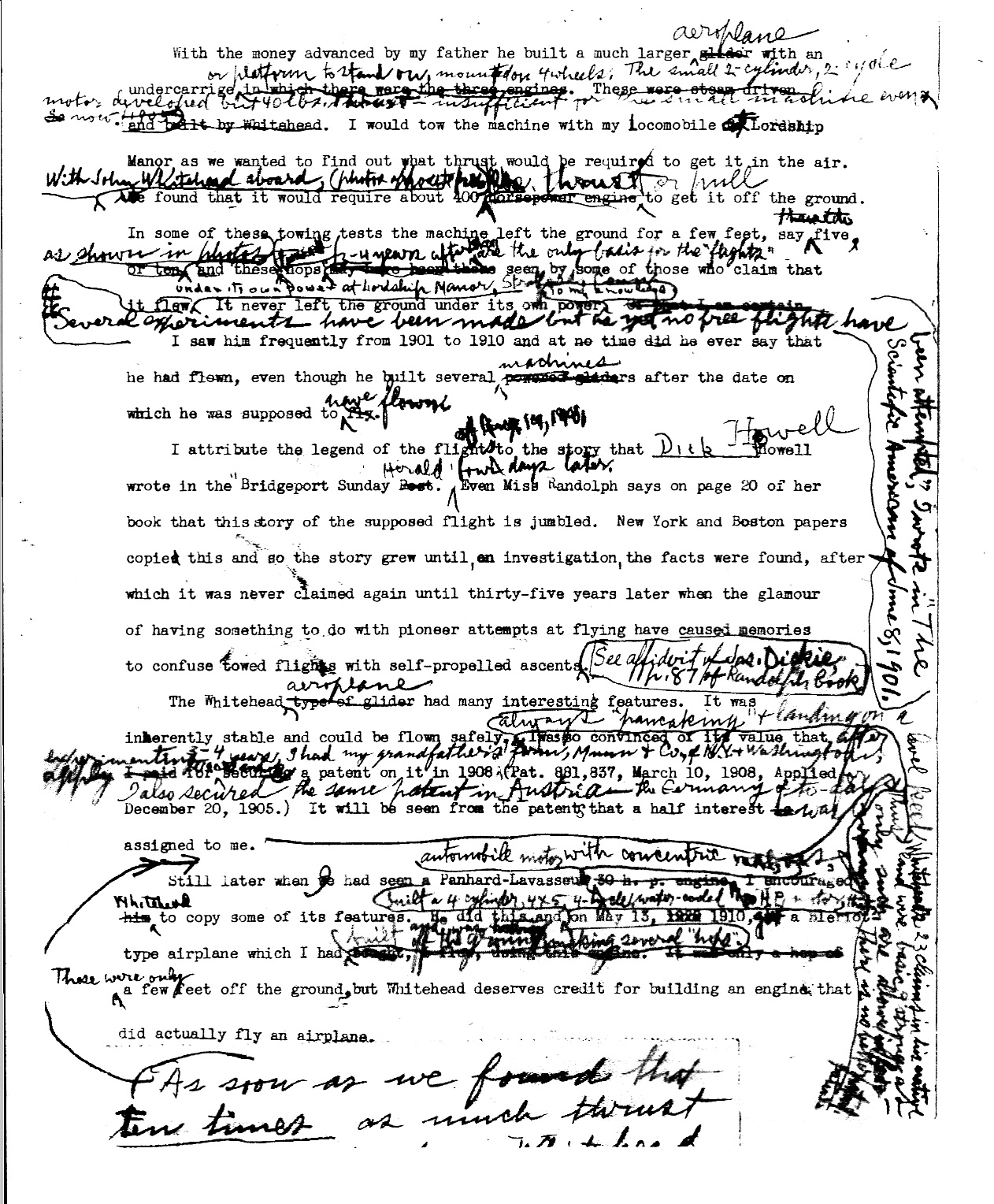

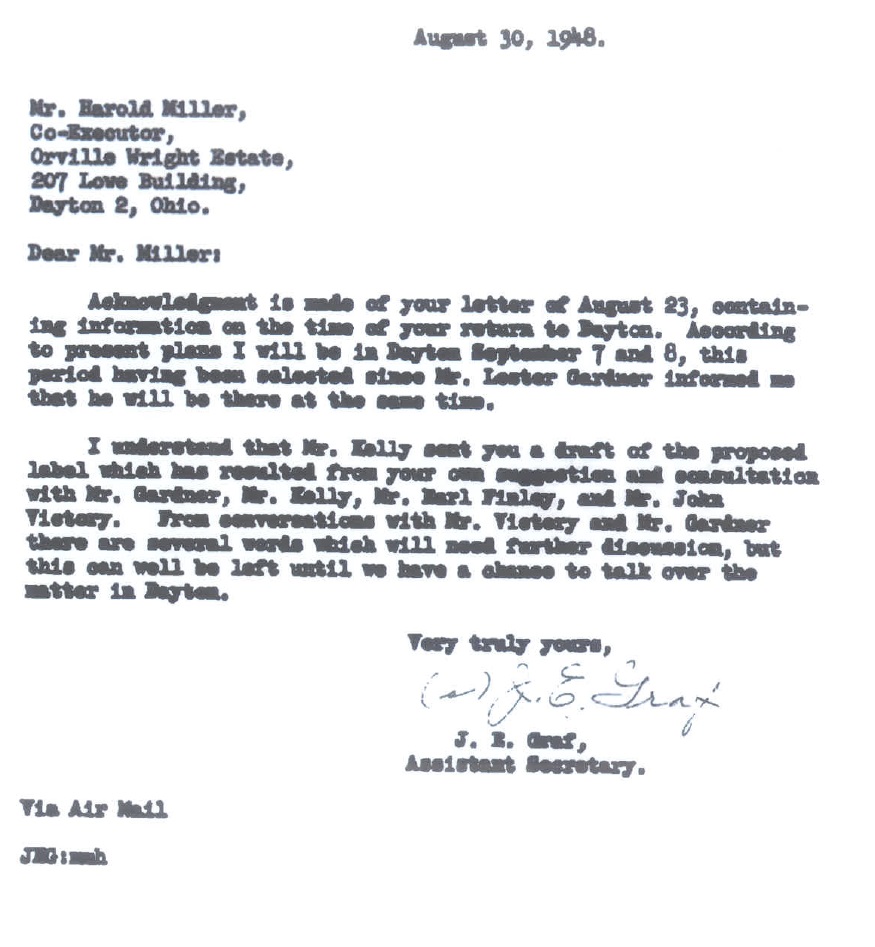

Below is a letter sent in August from Smithsonian’s Assistant Secretary, naming Gardner and Findley as parties to the ongoing process to determine the wording of the Wright Flyer exhibit labels, which continued through Sept. and Oct. of 1948. Additional documents obtained include transcripts of conversations and letters between the principal parties.

….. (letter continues to end):

![Lester Gardner replies to Graff that he will see Mr. Miller (co-executor of OW estate) on Tues. and if the changes [to the labels] are satisfactory to him and Ms. Beck [OW secretary] he will be glad to agree with them.](https://gustavewhitehead.info/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Gardner-to-Graf.jpg)

Lester Gardner replies to a letter from Smithsonian Asst. Secretary Graf that he will see Mr. Miller (co-executor of OW estate) on Tues. and if the changes [to the labels] are satisfactory to him and Ms. Beck [OW secretary] he will be glad to agree with them.

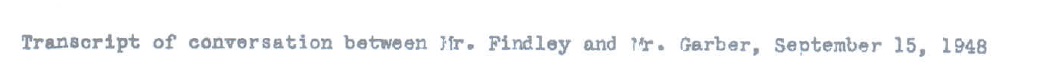

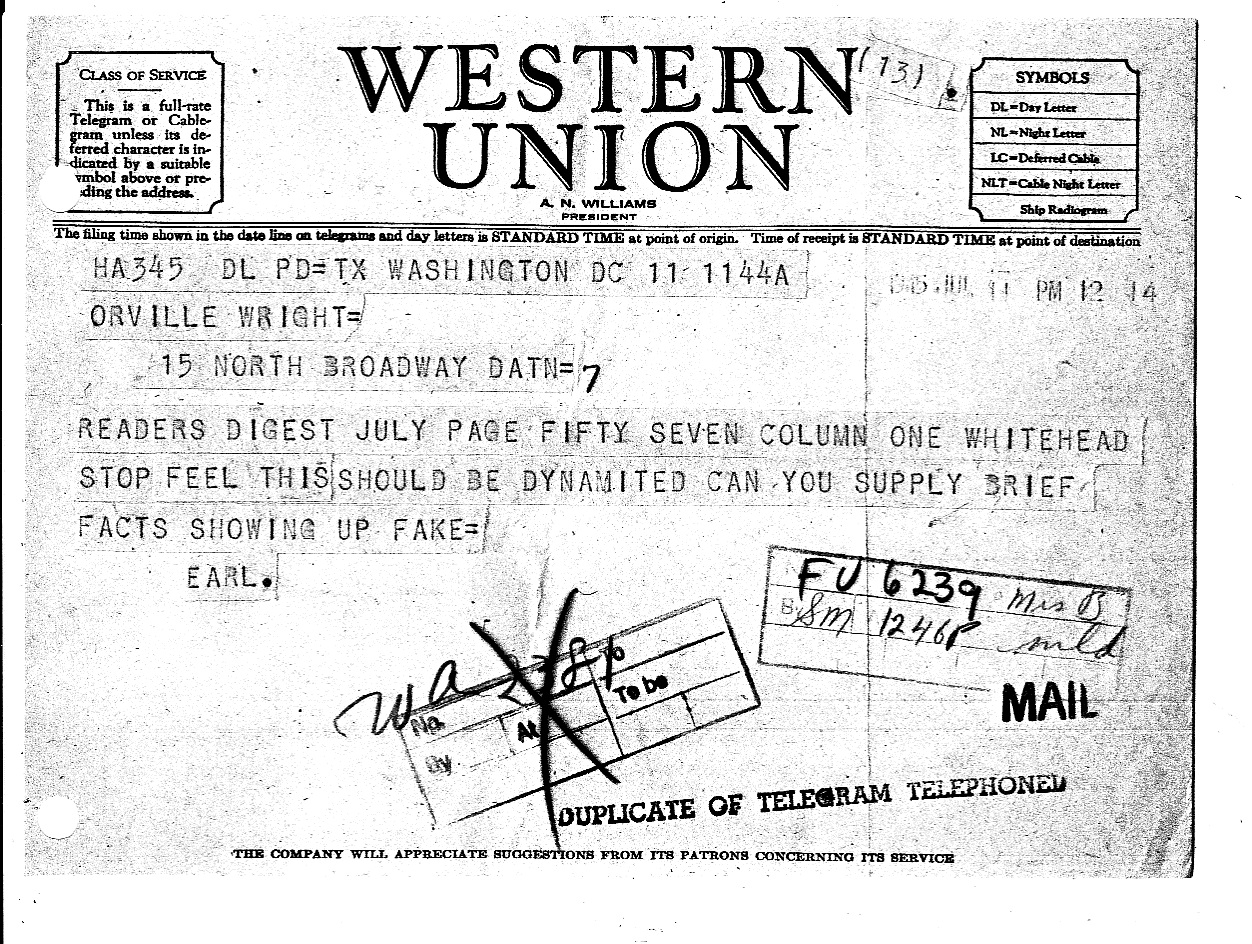

Paul Garber, key founder and a first curator of the Smithsonian National Air Museum (1946) reminds Findley he is there to represent Orville Wright, due to his close relationship. It is very important to note that Findley had sent Orville a telegram on July 14, 1945, three years before, where he asks Orville to help him “dynamite” the Whitehead claim that appeared in the Reader’s Digest of July, 1945.

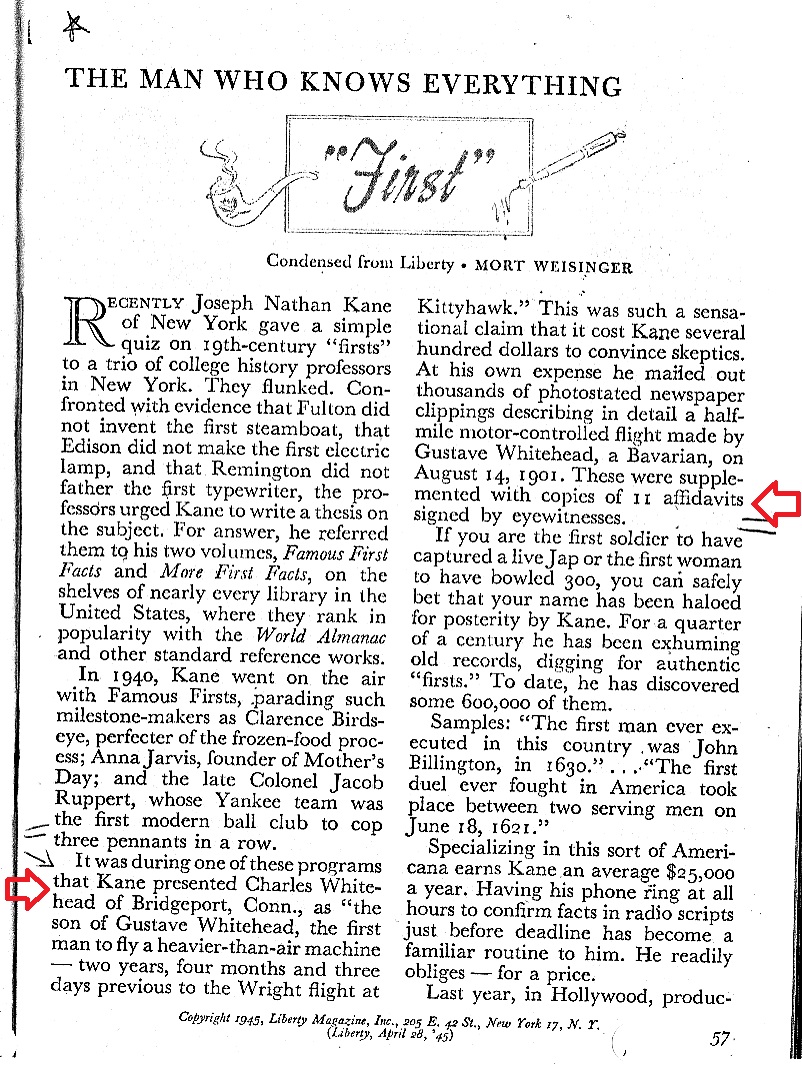

This is the “offending” Reader’s Digest article:

Originally published in “Liberty Magazine”, this Reader’s Digest column entitled “Firsts” mentions Gustave Whitehead claims recently covered in a coast-to-coast radio show featuring Whitehead’s son, Charles. Findley became upset and worked with Orville to correct this “problem”. Later, Findley ridiculed the Readers Digest editors and even mentioned trying to get them to retract the statements.

Earl Findley writes his good friend Orville Wright about the July 1945 Reader’s Digest article giving credit to Whitehead for first flight. Findley wishes to “dynamite” it. Asks OW to help use “facts” which Findley and Gardner had supplied him with in the so-called Stanley Yale Beach Whitehead Statement that Findley and Gardner had edited heavily.

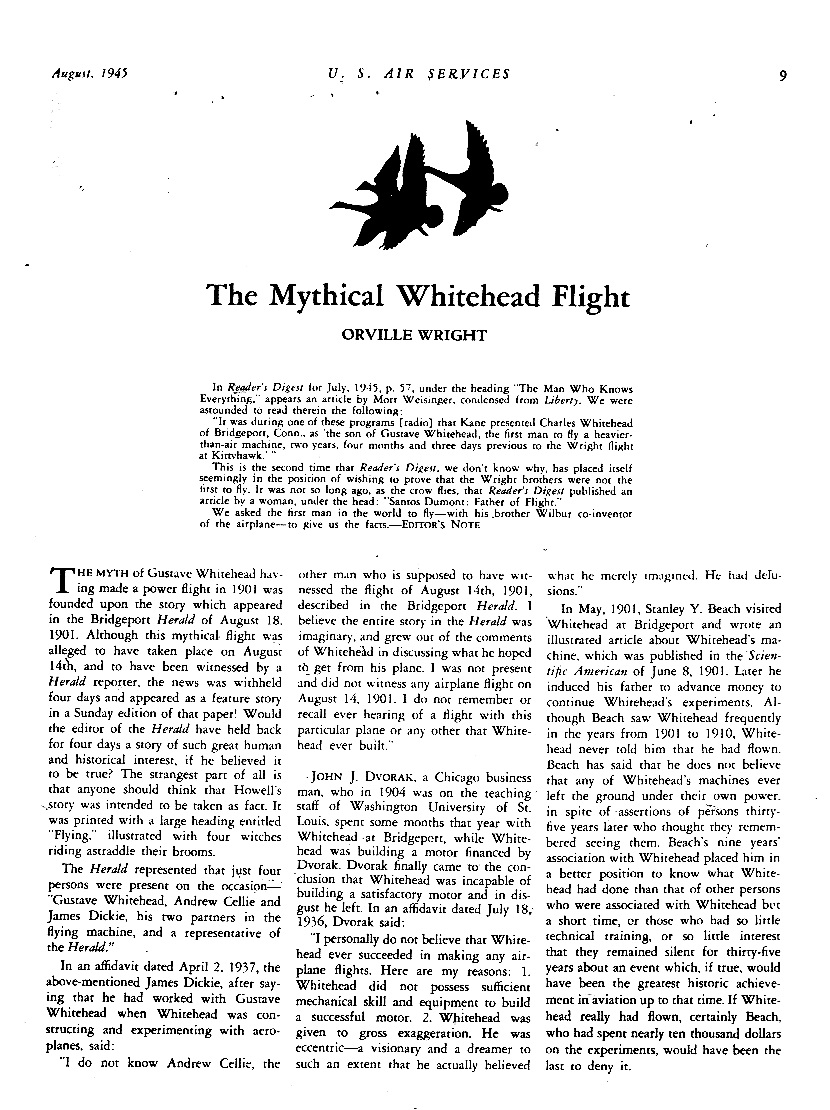

What evolved out of that suggestion was Orville’s inaccurate attack on Whitehead, “The Mythical Whitehead Flight” article published in Findley’s magazine in August, 1945:

Orville Wright’s heavily biased, misleading article, “Mythical Whitehead Flight”, part of scheme to discredit Whitehead, orchestrated by Findley and Gardner 1939-1945.

Earl Findley, in a letter to Orville on November 30, 1945, describes Whitehead supporters including Dr. Albert Zahm, very unpleasantly, as follows: “Zahm is still not the only ——- in the woodpile, but several snakes in the bull-rushes as well” [see below].Findley further lambasts Zahm, who has been improperly blamed for the Wbitehead claims, by telling him that the new Librarian of Congress wishes to find a younger man to take the place of Zahm…, then stating, “They couldn’t get a worse man than Zahm, even if they offered a reward of a million dollars for him. There isn’t any.”

Findley writes Orville crudely criticizing Dr. Albert Zahm of the LOC, who has been unfairly blamed for the Whitehead claims. Censored for 2014 audience.

Dr. Albert Zahm, professor of physics, was a highly esteemed national authority on early aviation, a chief of the Aeronautical Division of the U.S. Library of Congress, and a longtime critic of the Wrights, who’d published a treatise called “Early Powerplane Fathers” in 1945 that came close to crediting Whitehead for pre-Wright flights. Dr. Zahm wrote in May, 1944, ” It is technically possible, humanly very credible, that in 1902, Whitehead flew with petrol power.” Earl N. Findley was not only very angry at all the Whitehead supporters, including Dr. Zahm, but spent a decade trying to destroy the Whitehead claim to first flight and exact retractions. When he got his chance to develop a label that would forevermore credit Orville for first flight, it was the culmination of those efforts.

These are the missing links that shows “the Contract”, with the required Wright Flyer’s misleading label was directly aimed at denying Whitehead a chance for recognition as “first in flight”, having been developed by his foremost attackers within a small, heavily biased group. The above is only a small part of what is available at the Library of Congress and Smithsonian showing decades of collusion resulting in false credit for Orville Wright and the reasons why Whitehead never received credit nor even a fair evaluation from the Smithsonian.

1. More on “the Contract” here. (Fox News, Apr.1, 2013)]

2. Visit www.historybycontract.org on the Wayback Machine for more information on the Smithsonian-Wright Agreement of 1948.

3. Transcript of Conversation between Mr. Findley and Mr. Garber, September 15, 1948 (NASM, Smithsonian)

4. Wrong With Wright: Smithsonian Under Fire For Wright Brothers Contract (Jonathan Turley, April 2, 2013)

5. Read “Gustave Whitehead: First in Flight” (Brinchman, 2015), available on Amazon.com at https://www.amazon.com/Gustave-Whitehead-Flight-Susan-Brinchman/dp/0692439307, in print and ebook versions – contains an entire chapter on the history and development of this contract. Also available signed by author and in quantity at https://gustavewhiteheadbook.com/order-first-in-flight-book/.

This full article may be freely shared and posted under “fair use”, as long as it is complete and credited to Susan O’Dwyer Brinchman.

For media inquiries, contact gwfirstinflight (at) gmail (dot) com

© Susan Brinchman 2014 (Updated 2022)