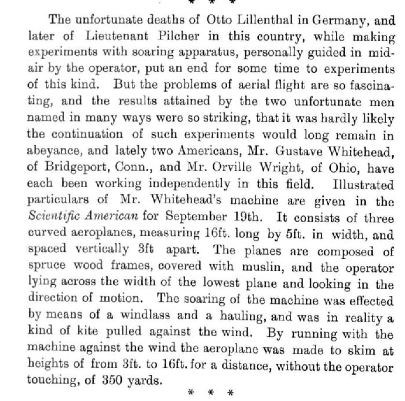

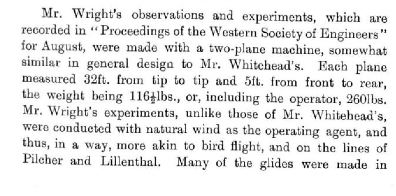

(January 7, 2022) A newly discovered engineering journal article (1) published in early October, 1903, reveals Gustave Whitehead was then accepted as making powered aeroplane flights ahead of the Wrights. The prominent journal, The Mechanical Engineer, a British illustrated weekly journal of mechanical and electrical engineering, edited by William H. Fowler, published by the Scientific Publishing Company in Manchester, UK from 1897 to 1917, supported the Scientific American’s report of September 19th, 1903 (2), crediting Whitehead with powered flights made in late summer, 1903. Describing Whitehead and the Wrights as the two then-most-prominent aviation experimenters, the article credits Whitehead with “running with the machine against the wind, [his] aeroplane was made to skim at heights of from 3 ft. to 16 ft. for a distance, without the operator touching, of 350 yards.” This account is confirming the journal’s acceptance of the Scientific American’s Sept. 19th detailed reports of Whitehead’s then-recent powered flights, including extensive information about the engine used. The descriptions of the Wrights’ efforts in this Mechanical Engineer’s article only mention gliding (without power), not use of an aeroplane with an engine (heavier-than-air machine with power), as indeed, that addition did not occur for the Wrights until December 17th, later in that year.

As in 1903, both the engineering world and the world-at-large were focused on longer, more practical flights that could transport people and goods, these modest but very significant successes by Whitehead were not recognized at the time as “firsts”. It would be a decade or more before who made “the first powered flights” would be fought over in courtroom battles well beyond the means of the humble Whitehead – with the Wrights aiming for that credit, in order to be allowed broad patent rights that could lead to their goals which included control of world aviation with handsome profits.

Gustave Whitehead’s experiments during the summer of 1903, described in local newspapers, the Scientific American, and The Mechanical Engineer, reveals the usual stages he employed in his invention process – first developing a full-sized workable glider that could be safely piloted by an operator, and then adding a lightweight motor to the design, to accomplish unmanned, and then manned powered flight. Whitehead had used this method for the previous decade, as it worked well for him, and would continue to do so throughout the next decade, as he invented scores of designs in this manner, hoping to develop a practical manned, powered flying machine, an aeroplane to transport people and goods to distant places. These early steps were not considered, in 1903, to be the successes we now see them as. The baby steps of early aviation were being accomplished, and were accepted and memorialized in engineering and scientific journals of the day, as well as the daily news and other mass media of the time. This Mechanical Engineer article, tellingly, also reveals Gustave Whitehead as one of two recognized aviation inventors of the day – on a par with (and actually exceeding) Wilbur Wright. Orville is not mentioned, as he was always seen as the lesser Wright at that date – though much later, especially after Wilbur’s death in 1912, Orville craved and sought the unearned title of “first in powered flight”, finally achieved post-mortem, through a highly questionable legal contract between his heirs and the Smithsonian.

Gustave Whitehead was credited in September and October of 1903, by some of the most esteemed journals of the times, with recent modest powered flights launched against the wind by a windlass and hauled by helpers with a guiding rope, no less than those alleged to be made by the Wrights on December 17, 1903, in a stiff breeze of 20 mph. The most important difference we might now point to is that this article is another very credible report of Gustave Whitehead being successful ahead of the Wrights. Whitehead’s well documented flights of 1901 – 1903 should NOT go unrecognized. This is but one more example of why Whitehead – not the Wrights – should go the title of “first in powered flight”.

For more information read “Gustave Whitehead: First in Flight” (Brinchman, 2015) available on Amazon in print and Kindle versions, and to order a signed copy, visit www.gustavewhiteheadbook.com.

(1) The Mechanical Engineer, October 3, 1903, p. 445

(2) Scientific American, Sept. 19, 1902, p. 204 https://archive.org/details/scientific-american-1903-09-19/page/n7/mode/2up